by Terry Wieland

Titles can be tricky. For quite a while, I pondered the idea of calling this one “The Stepford Wife of Rifles,” but decided that would confuse anyone not of the right age, and we are trying to make this accessible. The idea that a piece of walnut might actually be too beautiful — well, that should intrigue anyone who has ever admired a fine walnut stock blank.

The story begins in 2004, when I was possessed by a desire for a trim, handy deer rifle in .250-3000, built on a short Dakota bolt action. I laid out $1,000 for a stock blank, sent it to Dakota with instructions, and drove out eight months later to pick it up. Alas, someone had not read the instructions and the resulting rifle was a travesty. I refused to accept it, and to compensate me for the blank, Dakota gave me one of their No. 10 single-shot actions.

I pondered what to do for a couple of years, until my good friend Bill Dowtin (now the late Bill Dowtin, alas) offered me a stock blank that he’d had for some years and never sold because it was so good he had no idea how to price it. He thought it would be perfect for my purposes.

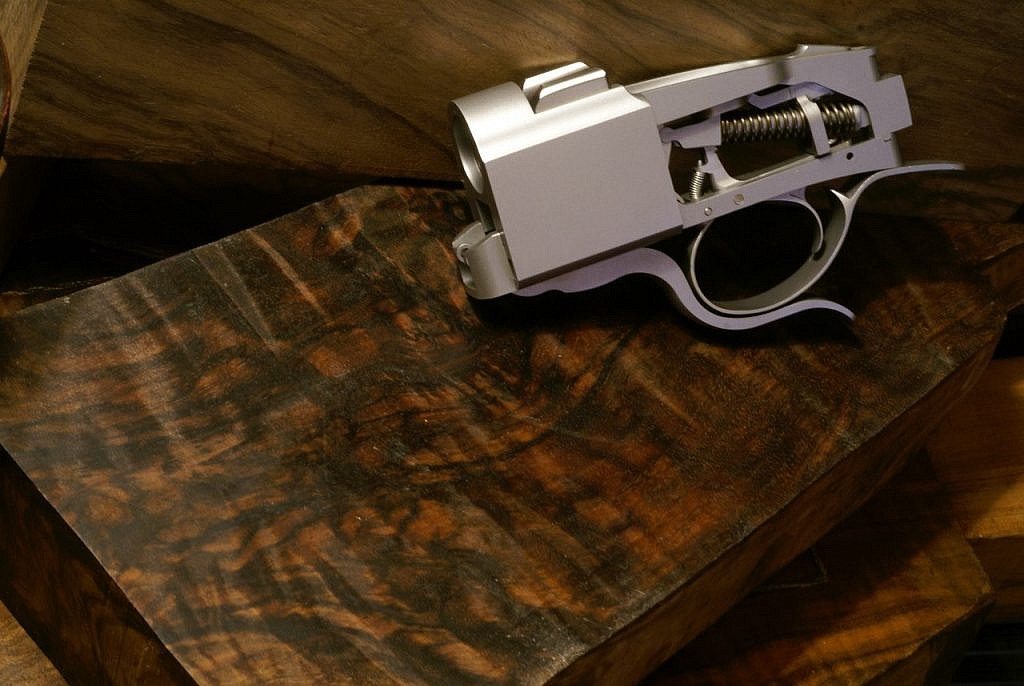

James Flynn, the now-retired gunmaker of Alexandria, Louisiana, agreed to make the rifle, and the result was a single-shot in .250-3000, with a quarter-rib, no iron sights, and two interchangeable scopes in mounts.

For those who have never seen “The Stepford Wives,” it is a morality tale about men who are given the “perfect” women, only to find that perfection can be tedious and unfulfilling. In a trick the gods of gunmaking sometimes play on us mortals, the rifle was undoubtedly gorgeous, and beautifully made, but it was virtually unshootable, at least in the way I had intended. Wearing a scope, it did not carry easily in the hand, and its 24-inch, small-profile barrel made it so barrel-light it was impossible to shoot accurately without a rest.

In other words, we had arrived at almost the exact opposite of the trim stalking or still-hunting rifle I had in mind. (Counting the aborted Dakota, that made me oh-for-two in that department.) A couple of years later, I gave the rifle to Bill as a thank-you for all the help he’d given me over the years, and he sold it to finance a new pickup. Where it ended up, I have no idea.

Unfortunately, I have no full-length or finished-rifle photos, but the ones you see here are more than adequate to illustrate both James Flynn’s workmanship and the look of the walnut stock — which was, after all, the purpose of the whole exercise.

As I recall, the blank originated in Armenia, and had been cut there many years before it came into Bill’s possession. The Armenian wood dealers themselves did not know what to make of it. For a long time, they kept it hidden from their Soviet masters, and brought it out only when the Soviet Union went belly up and Armenia became independent and quasi-democratic.

The responsibility of what to do with it weighed on both Bill and me, and I can’t rid myself of a nagging guilty feeling that we did not do it justice. But then, maybe that was just not possible.

______________________________________________________________________________

Terry Wieland has been Shooting Editor of Gray’s since 1993 and is the author of a dozen books on hunting, shooting, and history. His latest is Great Hunting Rifles — Victorian to the Present, published by Skyhorse in 1997. Last year, Skyhorse reprinted his acclaimed 1999 book on Robert Ruark, A View From A Tall Hill.