by Greg Thomas

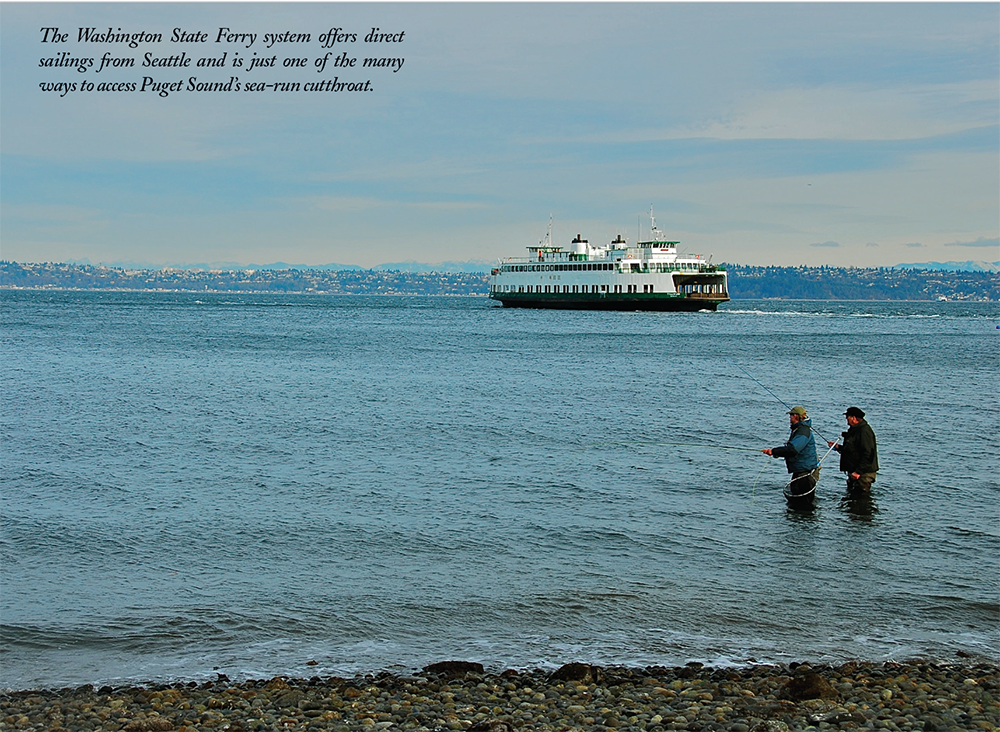

Casting for sea-run cutthroat gives anglers a taste of the Pacific Northwest.

I met Dave McCoy on a chilly winter morning south of Seattle, when I‑5 was covered in black ice, and vehicles were strewn about the median like flotsam.

Some were overturned, while others pointed in the wrong direction, head‑ lights carving through ice crystals and into the evergreens. McCoy didn’t care. He steered the Suburban down the interstate, past Tacoma and Tumwater, as though he were driving on sandpaper, all with a 17‑foot drift boat trailing behind.

I’d known them for all of an hour.

Days earlier, we’d met at a local fly shop and hastily agreed to fish the Cowlitz River for winter steelhead. Now we headed down the road together with one thing in common: fishing. And that was enough. We didn’t catch any winter steel that day—didn’t even touch a fish, in fact—but we formed a friendship that paid off later. McCoy called the following winter and said, “When you’re in Seattle, let’s hit the sound for sea‑run cutthroats.” We’ve been fishing together ever since.

Sea‑run cutthroat are the Pacific Northwest’s least appreciated fish, mainly because so many West Coast anglers can’t get salmon and steelhead off their minds. And when they do, their efforts most often take them to the dry side of the mountains, to Eastern Washington and Oregon, or north to British Columbia’s Kamloops country, for non‑native trout.

Not that rainbows, browns, and Lahontan cutthroat aren’t worthy targets. Who knows how many hours of life I’ve bobbed away in a float tube, fishing desert lakes—Lenice, Lenore, and Dry Falls, among others—specifically targeting those species. But as a natural‑ born son of the Pacific Northwest, and having spent a good deal of my life in Southeast Alaska, I visualize fog, and ice, and rain pattering on rotting maple leaves when fishing this region.

I dream of foghorns, the drone of seaplanes taking off from Lake Union, and orcas blowing air into that chilly Puget wind. I imagine buoy markers heaving to and fro in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, their bells clanging in unison. I hear sea lions barking and gulls squawking, wind ripping through the tops of evergreens, and maybe a little cry from Kurt Cobain, his voice blaring through someone’s cheap‑ass speakers from a rusted‑out Nova parked on a beach, weed smoke peeling from a slightly cracked and heavily tinted window.

Like all those things, a native sea‑run cutthroat, spawned in freshwater streams and growing to maturity in salt water, is real Northwest DNA. It’s a fish that ranges between 10 inches and two pounds on average, can grow to five pounds or more, and fights well above its weight class.

Growing up, I fished sea‑runs in Hood Canal, between Seattle and the Olympic Peninsula. We rowed heavy wooden boats and trolled a contraption called pop gear, which consisted of in‑line spinner blades that turned in unison, trailed by a snelled hook holding a worm. You rowed the boat, trolled the gear, and sometimes knew a sea‑run had taken the bait. Other times, the blades fought harder than the fish. I was only one in a long line of family members who’d caught sea-runs in that fashion, and my grandmother, who died at 103, was still trolling pop gear well into her 90s.

On one occasion, when I was just getting into fly fishing and so badly wanted to entice a sea-run on the fly, she reminded me: “If you want to catch fish, you troll the pop gear.” We’d gone about an hour without a strike before she shelved the fly rod and whipped out Old Reliable. She soon brought a really nice cut- throat to hand, a 17- or 18-inch fish, and it never swam again.

My grandmother grew up with four brothers on a dry farm in Southern Idaho, where food was tough to come by. To her, the chance to eat a sea-run cutthroat was always a gift. Habitat deterioration around Puget Sound, mostly from logging practices and massive population growth, jeopardized the cutthroat in the 1980s and 1990s.

Then, around the turn of the century, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife placed catch-and- release-only restrictions on sea-runs, and the fish quickly bounced back. It’s not yet out of the woods in Western Washington, where urban sprawl still outpaces environmental sanity, but it’s hanging tough throughout most of its native range, and anglers are having a field day catching these fish, along with resident cohos, from the beaches.

In Oregon, up the coast in British Columbia, and Southeast Alaska—the sea-run’s stronghold—the fish are faring well. In any of these places, anglers might land a half dozen fish in a day, sometimes more. In the spring, especially in April and May, sea-runs gather along the lower ends of rivers and streams, including the estuaries be- low them. There, the cutts feast upon juvenile salmon fry and smolts as they head out to sea. Anglers who fish simple patterns to match the small salmon are often rewarded.

During fall, sea-runs head up the Northwest’s rivers and streams to spawn. But I’ve rarely fished for them there, instead choosing to walk the lonely beaches or drift shorelines in a small open skiff, casting to points and current lines, or to places where birds are working bait.

One can enjoy fishing that way during winter, too, when sea-runs feed on any baitfish they can find, plus small shrimp, crabs, and mollusks. When you hook one of these fish, especially on a light rod in the 4-to-6-weight range, you’ve got something special. Anglers in the know agree this fish battles as hard, pound for pound, as any steelhead or salmon.

Too bad there isn’t more size to them. A four-pound fish is a giant; a five-pounder is a once-in-a-lifetime catch, and anything bigger is a unicorn. It is often said that five-pounders don’t exist, but there is a 16-millimeter film, old and grainy, at my parents’ house that proves otherwise. My father and his older brother are shown holding a line strung through the gills of a couple of sea-run cutthroat, and there is no doubt in my mind—and my father can attest—that those fish each weighed five pounds or more.

Once, while I was targeting steelhead on Haida Gwaii, my fish-freak friend from Montana walked downstream and returned to nonchalantly declare, “I just caught a real nice cutthroat upstream.”

“How big?”

“Probably twenty-three inches.” “What!”

Alas, no photo. But it proved fish that size still exist.

Many anglers prefer fishing sea-runs during fall because they can be caught in fresh water, where steelhead and salmon might also be targeted. There, of course, the cutts will take dry flies, but they’ll eat drys in salt water too. Some of the best days of my youth found me drifting a tiny bay off Wrangell Narrows near Pe- tersburg, Alaska, where I discovered beer and everything else one might expect an unsupervised 16-year-old to find. There, I’d sip Raniers, spot cutthroat feeding just off the popweed, and lay a Jackson-Cardinal in their line of travel. One twitch at the right time would almost always result in a topwater take.

These days, many anglers in the Puget Sound and elsewhere are throwing mini Gurglers, Sliders, and an array of poppers. Sea-runs feed near the beach, usually within a long cast from shore, and they are aggressive predators. If they see a commotion, especially if it appears to be an injured baitfish, they’re quickly on it. That’s why it often pays to cover ground when searching for these cutthroat—they have to be opportunistic to survive.

If you make a few casts in a particular spot and don’t get an eat, it makes sense to move. However, if you find a likely spot, maybe at the mouth of an inlet, or in an estuary, or over an oyster bed, or where the current—at a particular stage of the tide—rips nicely around an exposed rock or point, then you should keep casting and let the fish come to you.

With all that’s happened in the Pacific Northwest—the sharp decline of so many salmon and steelhead runs, increasingly crowded rivers, and competition at an all-time high—sea-runs provide an appealing option.

McCoy, who runs Emerald Water Anglers in West Seattle and guides throughout Western Washington, says if he could fish only one species, it would be “Sea-runs, no doubt.” That observation fits his pace; he enjoys the salt water; he gets a thrill seeing trout smashing poppers on top; and he really admires the coloration of these fish, a vibrant mix of green, yellow, tan, and orange.

As for me, fishing sea-runs takes me back to the 1970s and early 1980s, when Seattle had three professional sports teams and fewer than a million people. You could travel I-5 or I-405 anytime without delay. Homes with a view were available for $40,000.

Much of that has changed, but when I’m on those beaches, or at the head of a small bay near the family cabin on Hood Canal, watching for signs of fish on an incoming tide, I can see, at least momentarily, that there are still some places in Western Washington that remain mostly wild and free. At times like those, while casting into the salt, it’s easy to believe that anadromous fish runs could go on forever, and that my grandmother didn’t catch the last wild fish in the sea.