by Terry Wieland

The annual gathering at the Jack O’Connor Hunting Heritage Center in Lewiston, Idaho, is part fan club, part fund raiser, part social event, part book club, and part gun show. Mostly, though, it’s an effort to promote O’Connor and his ideas on hunting.

At this point, one would usually throw in a line about O’Connor needing no introduction, but guess what? We’ve reached a stage where he does need an introduction, most particularly for anyone under 50. O’Connor died 45 years ago, and though his work lives on in old magazines and, especially, his books, you have to go looking.

This is unfortunate because Jack O’Connor, during his 31 years as shooting editor of Outdoor Life (1941-72), was unquestionably the most influential hunting writer in America. He did not invent the .270 Winchester, but he made it famous and enormously popular; he did much the same for the Winchester Model 70. To his later regret, he also, almost single-handedly, made sheep hunting the goal of every serious big-game hunter. He did for wild sheep what Ernest Hemingway did for the running of the bulls in Pamplona—not an unalloyed evil, but not good, either.

That, however, was unintentional, and it could be argued that, while the pursuit of the “Grand Slam” of wild sheep has become a huge-money game of status and chicanery, it also led to serious efforts to conserve wild sheep and reintroduce them where they’d been eradicated.

What set O’Connor apart from other giants of the gun-writing world was his sheer ability as a writer. The man was a magician with words—deceptively plain-spoken and simple, but irresistible. He not only put you there on the mountain with him, he left a picture you never forgot.

One of my favorite passages describes a pack trip in the Yukon, riding through the mountains in wind and snow. He arrived in camp after twelve hours in th saddle, wet and shivering, to find one of the guides had just prepared a hot bannock. He soaked it in butter and later wrote, “Nothing I have ever eaten tasted better.” I’ve been trying to perfect my bannock-making ever since—alas, to no avail.

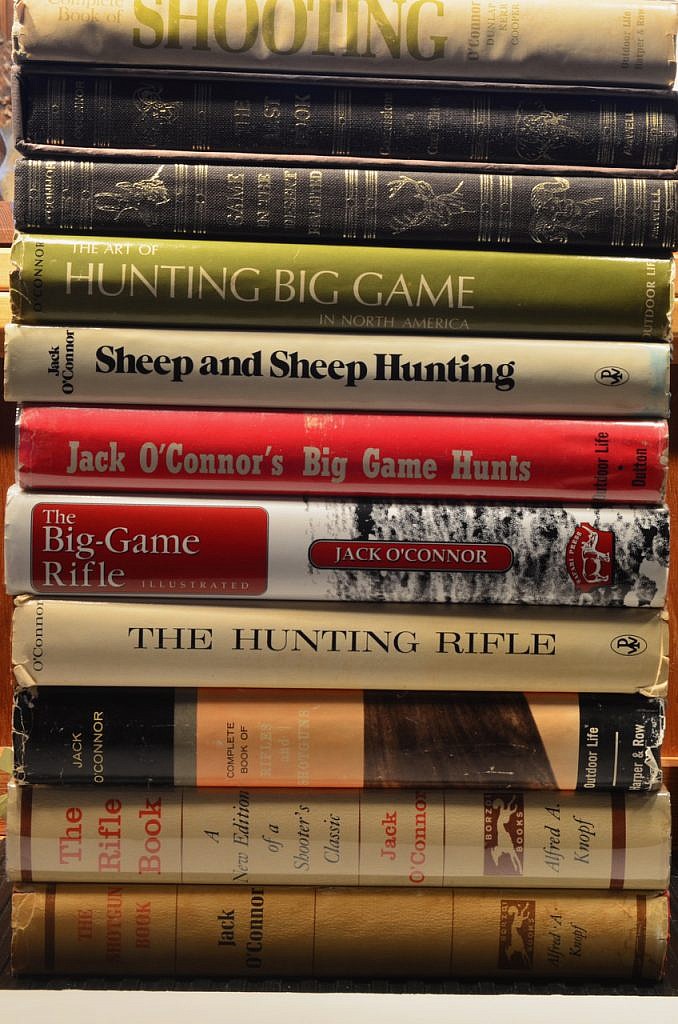

During his life, Jack O’Connor wrote a dozen books on hunting, rifles, shotguns, and big-game animals. Most of these were offered through the Outdoor Life Book Club, and sold in the tens of thousands—unheard of numbers for gun books. One, The Complete Book of Rifles and Shotguns (1961), is reputed to have sold 325,000 copies! By 1963, it was in its tenth printing.

You can still find almost all of them, and for not much money. Anyone who does not have O’Connor’s large-format Big Game Animals of North America, with its beautiful (if somewhat retro) color portraits of the animals by Doug Allen, is missing something magnificent. Hand a kid a copy of that book, and if he doesn’t become interested in animals, rifles, and hunting, he never will. To say nothing of reading: Like all O’Connor’s writing, it’s easy to read, never talks down, and—most important—never gets old.

If this sounds like I’m an unrepentant O’Connor fan, you’re right. Second only to Robert Ruark, he had a profound influence on my life and actually, as I have now made a living writing about guns and hunting for almost 40 years, and never became a novelist like Ruark (an early ambition), maybe O’Connor was actually the more important of the two. Either way, it doesn’t really matter.

After Jack O’Connor’s death in 1978 at the age of 76, his heads, horns, rifles, books—even his typewriters—were left to an Idaho university, where they were on display for a while. They then went into storage, were rescued by Leupold & Stevens and put on the road as a traveling museum. In 2007, the O’Connor center was established in Hells Canyon State Park, on the Snake River just outside Lewiston. Since then, with a small but full-time staff, it has worked to promote not only ethical hunting (an O’Connor priority) but interest in conservation and, not least, the craft of writing.

The center has a website (www.jack-oconnor.org) which gives a full picture. I just got back from the annual fundraiser, which includes a dinner, auction, the usual stuff. Hardly worth driving 3,894 miles for? You might be surprised. Aside from the social aspect, the great circle route up through Wyoming and Montana and over the Lolo Pass into Idaho, then back down through Idaho and Utah into Wyoming is worth it every time. And if you’re stopping for dinner in Lexington, Nebraska, Kirk’s Nebraskaland Restaurant has prime rib every day of the week.

Wieland discovered Kirk’s on the way out, and timed his return to hit Lexington just at supper time. Life is an adventure.