The ravines spread out and up like the fingers of a starfish. Partway up, a huge granite chimney blocked our view of the high cliffs, but Eduard and I began picking our way up, keeping an eye on the slopes above. Halfway, with no sign of the aoudads anywhere, we were about to turn back when I spotted a glint of horn under the high cliffs near the far end. They were undisturbed, and several were rams.

Moving slowly, we crept to our left to put the rock chimney between them and us. The aoudads were drifting slowly in our direction, so if we reached it undetected, I might get a shot. It was only about 200 yards away, but climbing was like balancing on ball bearings and jagged plates of rock. Every step carried the threat of my feet going out, and half the time, we slipped back about as much as we climbed. Among the rocks lurked a dozen varieties of cacti, just waiting.

We made it to the chimney, crawled up into a crevasse, and crept through to look out the other side. The aoudads were gone. There was an opening in the cliffs where they could go up and over, and they had done just that. Eduard and I made our way along to the opening, and went up and over ourselves. Atop the mesa, there were a few quail, a whitetail buck lounging under a tree, chewing watchfully, and a magnificent view across the ranch to the far mountains. But no aoudads.

The trip back down was far worse than the climb up. Every step was a trap, every rock was ready to roll. Soon, my legs were cramping with every step. One bad tumble gouged my rifle stock and bruised a hip, and when we made it back to the 4×4, it was close to noon. That up-and-down was one of the longest thousand-yard round trips of my life.

Cibolo Creek’s main building began as one of Milton Faver’s forts, complete with thick adobe walls and gunports. Fully restored, it

houses several small museums as well as the ranch’s living quarters.

WHEN WE WENT BACK OUT IN THE AFTERNOON, warm had turned to hot, and I discarded my Filson wool in favor of cotton. This is one hunting area where you might encounter anything from a blizzard to a heat wave. The winding track took us back up past the small lake, through the ravine, and then zigzagged through a gorge, climbing steadily past cliffs that would give a mountain goat pause.

We came out onto a high, grassy mesa—high enough for a long view out over the ranch, but still beneath the highest peaks of the Chinatis. Down below, the lake was a tiny, glittering sapphire. The track crept in and out along the mountainsides, sometimes traversing man-made slides of gravel—if granite tombstones can be termed “gravel”— that were as tough to walk on as drive over. At between 5,000 and 6,000 feet elevation, the air was noticeably thin to my midwestern lungs, and the wind gusted and swirled, raising dust devils. It was becoming hazy higher up. Any sane person would have been having a nap about now, and the aoudads seemed to agree. Every living creature, except for the odd circling eagle, was off drowsing under a bush somewhere.

The rifle steadied, I touched the trigger, the .250-3000 barked, and we heard the unmistakable thump of the bullet.

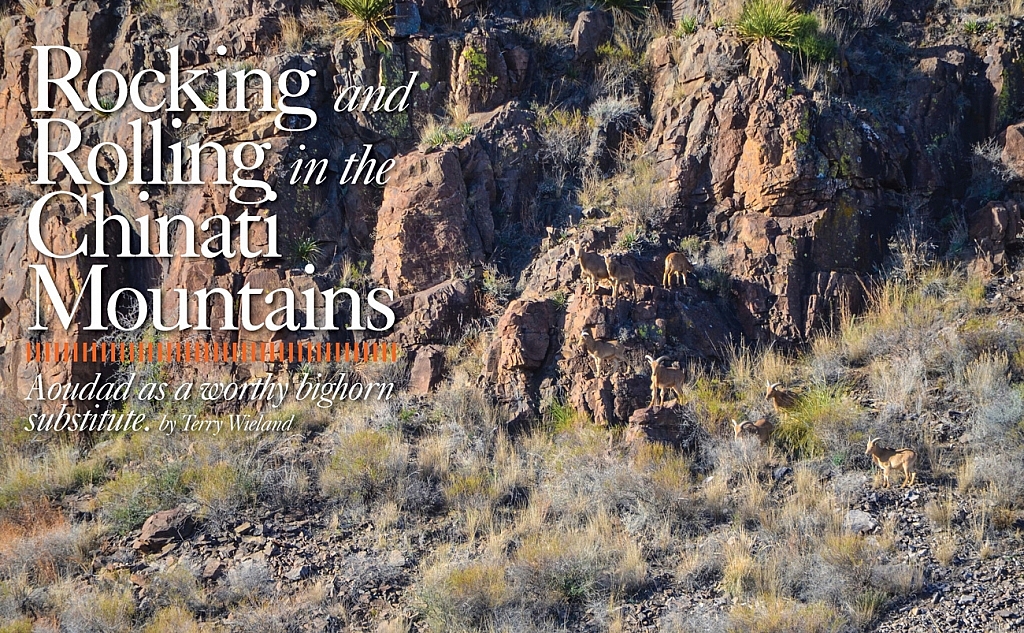

But then, in the “now we’re poor, now we’re rich” unpredictability of big game hunting, we came around a bend in the mountain track, and high above us, near the foot of the high mesa cliffs, was a clutch of aoudads. All rams, some good, and one really good. And, most important, undisturbed. They were far enough away, and high enough up, that they weren’t worried about us, although they knew we were here. We watched them and they watched us. Then they began to move slowly along the cliff, easing farther away.

On foot, Eduard and I crept along the road, hoping to cut the distance a little and maybe find a place where I could get a decent rifle rest. One second we were hidden behind a fold in the hill; the next we were out in plain sight. They were a good 300 yards away, up at a very steep angle—a tricky shot at the best of times. Then I found a boulder and a high bank where I could put my backpack and crouched down behind, peering through the scope.

“Which one?” I asked. Eduard was studying them through the binocular as they picked their way along.

“They’re all pretty good. . . .”

“Just tell me which one.”

Aoudad horns sweep out and back, and are measured across the center from tip to tip. This ram’s horns measured 30 inches across—an excellent trophy.

“On the far left. He’s moving. Now he’s stopped.”

“The one on the rock?”

“Yes!”

The rifle steadied, I touched the trigger, the .250-3000 barked, and we heard the unmistakable thump of the bullet. The ram dashed straight ahead for 30 or 40 yards, stopped, his back end dropped from under, and he slid backwards down the slope until his horn caught a low branch. He was 285 yards away when I shot. My rifle was sighted for 250 yards, but shooting uphill you need to hold a little low anyway. It all worked out perfectly. Sometimes you just get lucky.

IT TOOK THE BETTER PART OF AN HOUR for Eduard and me to pick our way up the mountain, negotiating rock slides, avoiding sprained ankles, refraining from grabbing at cacti for balance, panting in the thin mountain air, and all the time trying to keep our eye on the aoudad.

The branch holding his head up made it appear he was still alive, and I needed to be ready if he struggled to his feet. When we finally reached him, we found he’d been dead before he came to rest, with half his heart shot away. We struggled to get some pictures, and when Eduard gently unhooked his horn from the branch, he tumbled and rolled 50 yards down the mountain in a shower of rocks and dust.

Whether hunting aoudads in West Texas is a good substitute for desert bighorns, I’m not in a position to say. It was certainly demanding enough. But on one point I can agree with Jack O’Connor completely: You won’t hunt any rougher, more treacherous mountains anywhere— at least, not anywhere I’ve been.

If anyone would care to contribute $50,000 to the “Help Wieland hunt desert bighorns” fund, it would be gratefully accepted. In the meantime, there’s a big aoudad occupying the vacant spot on the wall, and he looks right at home.