Aoudad as a worthy bighorn substitute.

[by Terry Wieland]

ACCORDING TO JACK O’CONNOR, the desert mountains of the Southwest are the roughest hunting in North America. If anyone would know, he would: O’Connor grew up in Southern Arizona, but hunted mountains from Sonora to Alaska, including Idaho, British Columbia, and the Yukon. The ancient desert mountains of Sonora might not be the highest, or even the steepest, but what they lack in angle and elevation, they more than make up for in bruising, ankle-twisting treachery.

When O’Connor hunted Sonora, his favorite game animal was the desert big – horn, which today, most people can only dream of hunting. Populations are small, tags are limited, prices sky-high. In the 1962 Gun Digest, O’Connor wrote, “The average American today has about as much chance to get a legal desert big – horn as he does to catch a saber-tooth tiger.” That was more than 50 years ago, and the situation is little better now.

In the same article, O’Connor reflected generally on what makes a great big game trophy, and why:

“An animal must be impressive, difficult to obtain, relatively rare, and hunted in interesting country,” he wrote. “He should also have popular prestige, and it does not hurt if there is some danger connected with his taking.”

By these criteria, O’Connor felt no other North American trophy could compare with the head of an old bighorn ram with heavy, battered horns and a cold glint in his eye. In fact, he said of the world’s trophy animals, the only others that compete are the related wild sheep of North America (Dall, Stone), and “the fabulous members of Asia’s argali tribe, the red sheep and urial of the Middle East, and the aoudad of Northern Africa.”

The aoudad? Why not? By O’Connor’s requirements, the aoudad (now of West Texas as well as Morocco’s High Atlas) gets an impressive score: Its home turf is both interesting and dangerous, and it is hard to hunt. If a Texas aoudad lacks something in prestige, that’s all to the good. It means they don’t cost an arm and a leg—although hunting them may cost you an arm, leg, ankle, or any other breakable extremity.

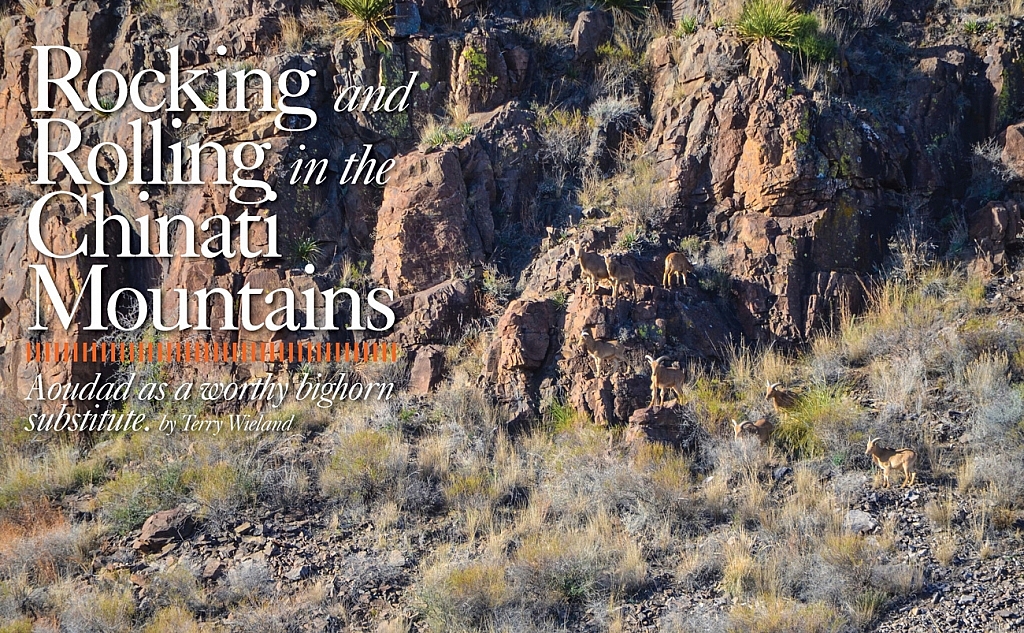

The Chinati Mountains of the Big Bend country of West Texas are ancient. Like other mountains of the southwestern deserts, they are rough, rocky, and treacherous. Jack O’Connor considered them the toughest of any in America for hunting. This is country for technical mountain boots, if you value your ankles. Every step, up or down, is a trap, with the cacti just waiting for your desperate, clutching hand.

The aoudad, also known as the Barbary sheep, is distantly related to North America’s bighorns. They were introduced to Texas in the 1940s, and like many other exotic species, soon escaped from captivity, took to the wild, bred with abandon, and settled into their new home for the long haul. Today, almost 90 years later, aoudads are spread throughout the rugged mountains of the Southwest. Being an exotic species, aoudads are not closely regulated by the game department, and hunting is left largely to the whim of the landowner.

Like the desert bighorn that formerly frequented these mountains, they are reddish earth-brown and blend into their desert surroundings; they have heavybased, back-curving horns, and a propensity for bounding around rocky cliffs and high scree, never missing a footing. In some areas, ranchers are eager to reduce their numbers because, except for being picturesque, they don’t contribute much. They consume the high browse that might otherwise feed the deer, and at least the deer are edible. What’s more, a good Texas whitetail rack is worth real money, whereas the aoudad—while attractive to other aoudads, I’m sure—is not in the same class, as a trophy.

For sheer hunting challenge at a reasonable price, however, you’d go a long way to beat the aoudad. And if you do put one on your wall, every time you look at it, you can remember what it was like out there, and reflect on the fact that you chased this beast on its adopted-home ground, and lived to tell the tale.

The Chinati Mountains lie in the high-desert Big Bend country of West Texas, north of Presidio. They are an ancient range—the highest is Chinati Peak, at 7,728 feet—and the years have not been kind. Unlike some other old mountains, the Chinatis have not worn down to gentle slopes and meadows. Instead, they are a jumble of steep, narrow gorges, hard-rock chimneys jutting to the sky, jagged cliffs, and endless scree. There is little or no forest: just cacti, coarse grass, and desert bushes armed with sharp thorns.

Water is at a premium in the Chinati Mountains. In 1857, an early settler named Milton Faver found a source of water here and established a ranch. He later found two more springs and built forts by them. His holding eventually grew to 30,000 acres, the largest in the district. The adobe forts afforded protection from roving Comanches and Apaches. With water, stout walls, and gunports, he could hold out indefinitely.

…we were about to turn back when I spotted a glint of horn under the high cliffs near the far end. They were undisturbed, and several were rams.

This property came to be known as Cibolo Creek Ranch. Today, it’s owned by a wealthy Texas businessman, and if the name seems vaguely familiar, you may have read about it earlier this year: Cibolo Creek was the ranch Justice Antonin Scalia was visiting when he died. Justice Scalia’s death prompted a spate of sensational pseudojournalism and conspiracy theories. Nothing like a gunport in an adobe wall to push city reporters off the deep end. One Washington Post story claimed to have torn away the “veil of secrecy” surrounding Cibolo Creek. How there can be a veil of secrecy shrouding a publicly accessible guest ranch is the only real mystery here. Maybe it was the air of opulence; that always gets them.

Having visited Cibolo Creek the week before Justice Scalia, I can attest to the opulence. Also to the quality of the accommodations (luxurious), the food (excellent), the service (friendly and efficient), and the overall atmosphere (authentically historic meets modern luxury).

This was all very well, but I wasn’t there for any of the above, delightful though it was. Our purpose in visiting Cibolo Creek was to pursue the aoudad. The ranch’s hunting guide having moved on the week before, the foreman, Eduard Martin, volunteered to take me out himself, so we were making it up as we went along. I was supposed to stay three days; even given the makeshift guiding arrangement, though, it says something about the hunting there, and the aoudad numbers, that they wondered what I might do on days two and three.

This suggests it was easy. It was not. Certainly, there were goodly numbers of aoudads. There were also black bucks (another immigrant), a few llamas, elk, and whitetailed deer. Heading out from the ranch, along the dirt track that wound up into the Chinati Mountains, we flushed coveys of blue quail that numbered into the hundreds, going up in a rolling cloud ahead of our 4×4.

At a rough elevation of 5,000 feet, it’s chilly there of a February morning, and it got colder as we climbed. Eduard drove up into the mountains, heading for an artificial lake made by damming the water where it fell into a steep, narrow gorge of the kind you don’t like to look down into (at least, I don’t). Like all desert waterholes, it’s an animal magnet. Sure enough, as we crept over a ridge to take a look, a flock of aoudads was picking its way along the shore, including two or three rams—one of them quite decent.

My aoudad’s horn hung up on a low branch. Unhooked, he tumbled and slid another 50 yards down the mountain. Aoudads are native to the mountains of North Africa and the southern Sahara.

Eduard looked at me with a raised eyebrow. This is the kind of dilemma I like, although I knew that if I didn’t shoot the one good ram now, I might be kicking myself two days hence, if I found myself with no ram and time running out.

“Shootable ram,” Eduard said hopefully. I looked at my watch. It was 8:52 a.m. on the first day. No, thanks.

As the sun rose into the cloudless sky, the last of the morning mist dissipated, and the high rock faces turned golden red. The brilliant colors crept slowly down until, finally, we could feel the sun on our shoulders. Our flock of aoudads was gone from the little lake, climbing back to lonely peaks. It gave me a chance to measure the range. Only halfway up, and they were already 500 yards away. Yes, indeed, come tomorrow or the next day, I might well be kicking myself.

The rocky track led down through a ravine flanked by steep mountains, with jagged pieces of granite threatening our tires every inch of the way. As we drove in and out of deep shadow, the temperature jumped up and down. We were shivering one minute, warm the next, and all the time scanning the slopes above. As we rounded a bend, we saw three big aoudads on a rocky outcrop. They whirled and disappeared as we ground to a halt. We were in a deep ravine that was shaped by the seasonal floods, with several other ravines leading out of it—all steep, all rocky. The sun had not yet topped the ridge. In deep shadow, we followed a creek bed lined with boulders, interspersed with thornbush, until we reached the entrance to the main ravine. There was no sign of the aoudads, but they might pop into view at any moment.