Gallery of North American Game

by Brooke Chilvers

As a child of midtown Manhattan, my first inklings of wild places were based on annual class trips to the hallowed halls of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). There, over the years, the elephants, buffalos, and baboons of the Akeley Hall of African Mammals became familiar old friends, and I still recall the newspaper headlines when the 94-foot, 21,000-ton model of a blue whale made its debut in the Milstein Hall of Ocean Life.

Yet even after learning about sculptor, taxidermist, biologist, and explorer Carl Akeley (1864–1926)—who famously did a life-size mount of the P.T. Barnum elephant, Jumbo, killed in a railroad accident, and saved his own life by strangling a leopard with his bare hands, and died of dysentery on an expedition in the Belgian Congo—I knew nothing of museum artist, illustrator, and painter Francis Lee Jaques (1887–1969). It was Jaques’s dioramas that had transported me, as a youth, from Australia to Peru to the Gobi desert. From the Alps to the Galapagos Islands.

Of the 80 museum habitat backgrounds he painted in his career—an estimated 30,000 square feet—during his 18 years at the AMNH (1924 to 1942) he produced 50, including all 18 in the Whitney Memorial Hall of Oceanic Birds, plus its murals and decorative maps. He painted its immersive domed ceiling, providing landscape for albatross, petrels and frigate birds, lying down on scaffolding, à la Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel.

Jaques had his reasons for resigning from the AMNH on the very day of his 55th birthday. Then he and his wife and collaborator, writer Florence Page (1890–1971), packed up the Upper West Side apartment where they’d lived for the last 23 years, and bought a house near St. Paul, Minnesota, where they could walk from the back door to their canoe. On a freelance basis, Jaques painted dioramas for Yale Peabody Museum, Boston’s Museum of Science, Welder Wildlife Foundation near Corpus Christi, and AMNH. For the (today’s) Bell Museum, he painted a dozen works celebrating Minnesota’s wolves on the rocky cliffs of the north shore of Lake Superior, the moose of Gunflint Beach, and the elk at Inspiration Peak.

Jaques (pronounced JAY-kwes, kwes rhyming with squeeze), who started life as an uneducated Midwestern farm boy, traveled on scientific museum expeditions, sketching panoramic landscapes from Panama and the Bahamas, to the South Pacific, Alps, and Arctic. He collected vegetation for the dioramas’ foregrounds, dressed and skinned specimens, and took measurements of just about everything, including altitude for his contour map of Pitcairn Island. He took photos of light and shadow play, made field notes, and created his carefully coded, “paint by number” color charts to work in tandem with his reputed photographic memory.

The modest Midwesterner met and mingled with explorers such as Osa and Martin Johnson, and artists, including William R. Leigh and Charles Livingston Bull, who sponsored his membership in the prestigious Salmagundi Art Club. But it was his late-life marriage to Florence, in 1927, that brought him the greatest pleasure: “We’ve never had any trouble about women or money and lived happily ever after.”

Jaques also did covers for Life magazine, Saturday Evening Post, Field & Stream, and especially Outdoor Life, producing its cover every month, for four and a half years, during World War II. That income, plus his museum pension, equaled his pre-retirement pay, which meant he and Florence could travel and write and illustrate titles such as Snowshoe Country (1944) and Canadian Spring (1947). He illustrated dozens of books, including five others by his wife, and three by Minnesota writer and conservationist Sigurd Olsen who, like Jaques, spent his honeymoon with his wife in a canoe on the Boundary Waters.

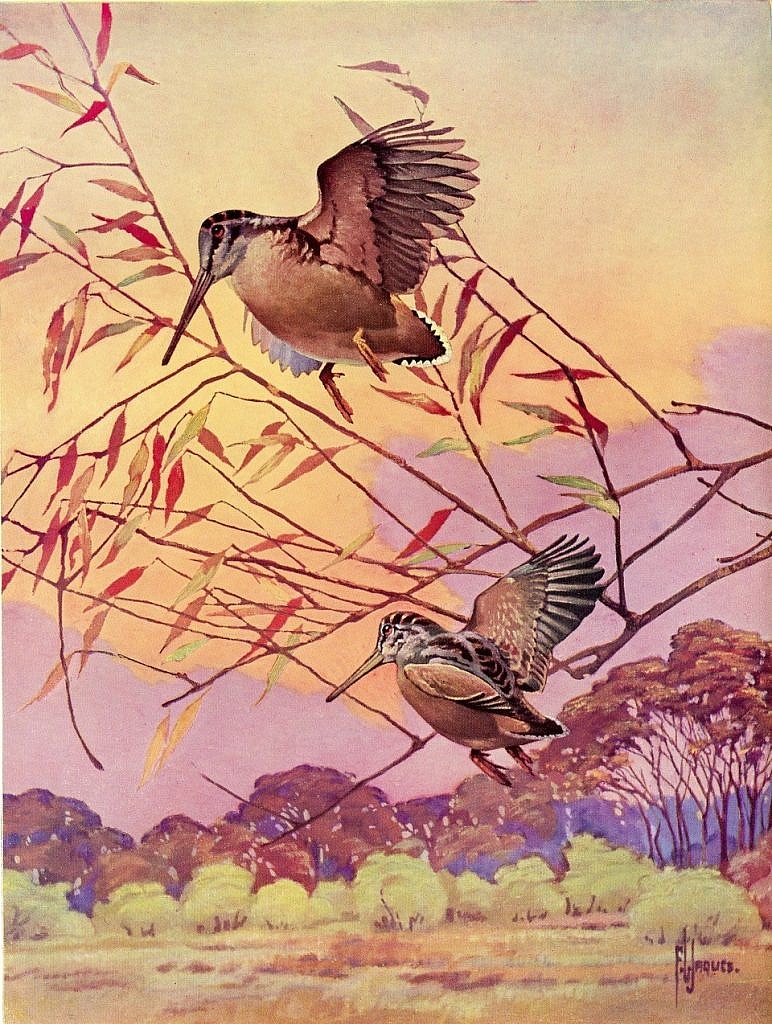

Yet never did it occur to me that the worn, oversized book with gold lettering and a whitetail on its cover, Outdoor Life’s Gallery of North American Game (1956), which was hotly disputed between my older brothers in the 1950s, and somehow ended up with me, was illustrated by Jaques, described on the front page as “foremost artist of the outdoors.”

The cover torn, the brothers long gone, it made a nostalgic and refreshing read, even after so many years. Alongside distribution, habitat requirements, and suggested calibers, “Where-To-Go” columnist P. Allen Parsons describes gunning for canvasbacks in a gale and galloping after fox. Of course, it is Jack O’Connor who tells us about Ursus horribilis, what they eat and where to find them, and how to kill them.

As a kid, I’m not sure I studied the texts, but I do recall the two woodcock bathed in an apricot light, and how at home the mountain goats seemed on their rugged ridges. Jaques had proven yet again his ability to place animals within their landscapes, rather than against them. Like his geese stretched over the prairie lakes, they seem to still have all of nature at their disposal.

Which leaves me feeling sad. Because it speaks of what was and what now is gone. Jaques wrote about progress: “I know—the country had to be developed, but we developed it very wastefully—we might have made it beautiful. It is, so far as we could make it, ugly.”

Brooke Chilvers is not sure the AMNH will be the same without its equestrian statue of Teddy Roosevelt at the entrance; and maybe that’s okay.