by Brooke Chilvers

Hunting fit for a Mughal emperor (Part One)

We refer to the first six of 21 Muslim warrior rulers that dominated large parts of the Indian subcontinent after 1526 as the Great Mughals. Theirs is considered the golden age of Mughal culture that encompassed Persian, Indian, and European influences.

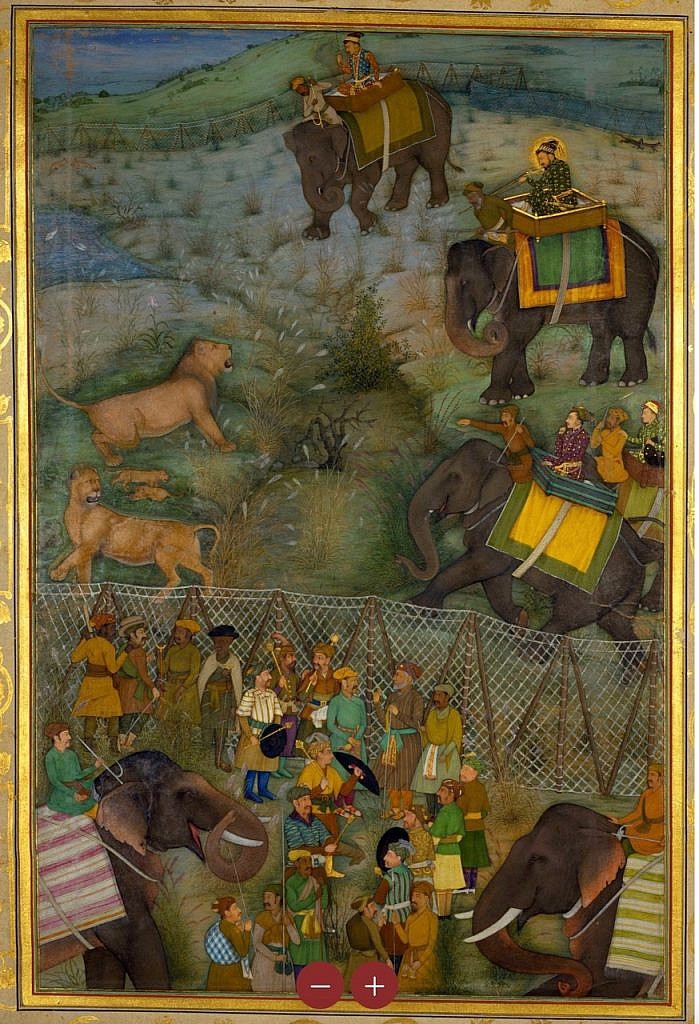

These emperors kept extensive official chronicles that describe and illustrate everything around them, from endemic diseases to their acute observations of nature. Illustrated with jewel-like miniatures executed in imperial workshops, these manuscripts preserve for us insights into those times.

Like all good emperors, the Great Mughals used hunting to display their warlike skills in weaponry and leading men, horses, and elephants into battle, as well as their expertise in keen strategy and tactics, and being favored by God with lucky outcomes. Three of them—Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan—were especially avid hunters, pursuing blackbuck, chital, and nilgai, as well as rhinoceros, lion, and tiger. They also captured and trained wild elephants and leopard.

Journals such as Akbar’s Akbarnama and Shah Jahan’s Padshahnama provide a picture not only of their preferred hunting methods, tricks and weapons, but also of the different landscapes, flora, and fauna of their empire. Gamebags were meticulously recorded by a scribe, including each animal’s sex, age and measurements, and where and how it was taken. Akbar’s game bag in 1567 in the Salt Range of Lahore includes blackbuck, markhor, urial, chital, nilgai, hares, and hyena.

It’s noted that Akbar killed 1,019 animals with his matchlock, nicknamed “Sangram,” alone—the very same rifle that led him to victory over the Rajasthani fortress of Chitor in 1568. His son and heir, Jahangir (1569–1627), was considered addicted to hunting (not to mention alcohol and opium). By age 50, he’d killed 28,532 animals and 13,964 birds, including 889 nilgai, 64 rhinos, 86 lions, 10 crocodiles and 3,473 crows. Once, in 1615, at the request of his guest, a Rajput prince, Jahangir shot a lioness through its eye.

Jahangir’s son and heir, Shah Jahan (1592–1666), is most remembered, of course, for building the Taj Mahal in memory of his third wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who died while giving birth to their fourteenth child. Although his court poet wrote that the yearning of prey to be killed by his arrows “was greater than the emperor’s desire for the prey,” illustrations show Shah Jahan hunting blackbuck, nilgai, lion and tiger.

Miniatures famously portray royal “ring hunts” called qamargah, based on an age-old Mongol combat tradition. These were month-long, rather martial hunting expeditions throughout the realm that required strict discipline and military-level organization to set up and operate the mobile palace and its hunting. Lines of luxury-laden caravans supplied the imperial family and its encourage of nobles, aristocracy, and its harem of innumerable female relatives, concubines, ladies in waiting, staff and servants, along with some 4,000 courtiers and soldiers.

Empire expansion and stabilization were always hard at work while emperors exercised their imperial authority over their dominion by very publicly hunting. Simultaneously, they not so surreptitiously exercised their armies. Thus, hunting was a form of diplomacy—with headquarters and infantry.