Every painting a dog’s tale.

[by Brooke Chilvers ]

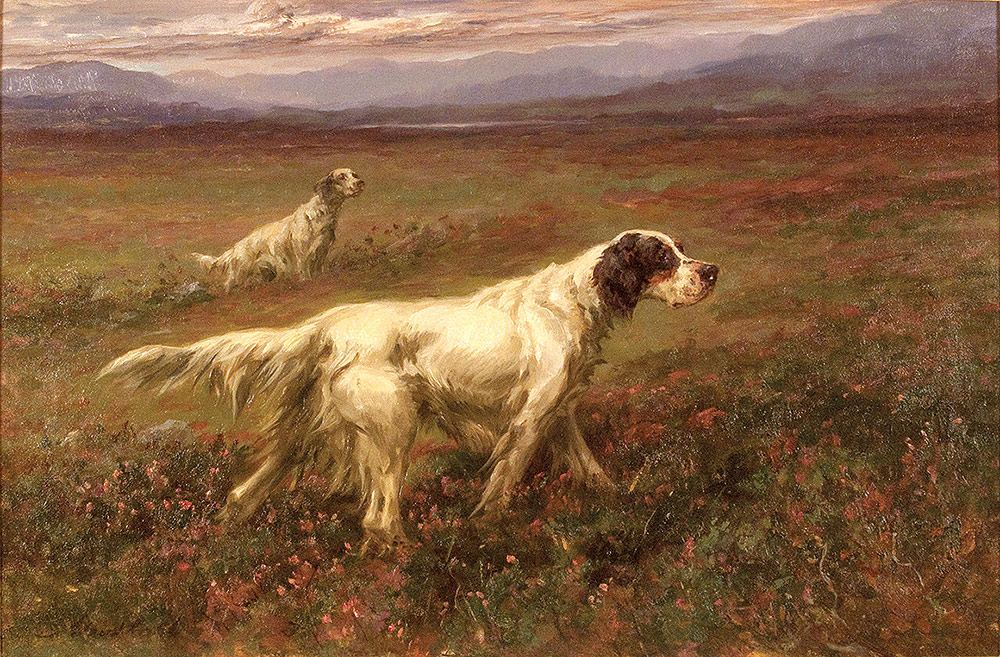

With a career spanning more than 50 years and both sides of the Atlantic, the prolific British-American painter Maud Earl (1863–1943), was her generation’s most preeminent and sought-after dog artist.

Maud was born in London, the only child from the first marriage of horse, dog, and sporting artist George Earl (1824–1908). George was a country gentleman, a keen sportsman, and a breeder of setters that his daughter cared for and cuddled at his country house in Banstead, Surrey, a horse-racing countryside associated with Epsom Downs. An early member of the Kennel Club (founded 1873), George made invaluable contributions to dog art, including The British Field Trial Meet, which portrays all the important breeders and fanciers of the day attending imaginary field trials in the rolling hills of North Wales. In the book Champion Dogs of England (c. 1870), Earl’s artwork serves as a precious record of each breed’s head type at that stage in its man-made evolution, and covers rare species like the Bedlington terrier and the now-extinct English white terrier.

Also within Maud’s circle was her father’s equally successful but less famous elder brother, the horse- and pet-portraitist Thomas Earl (1810–1876), with whom George sometimes shared a London studio. Thomas may have been the sporting art clan’s patriarch, which grew to include Maud’s half brother, racehorse artist Percy Earl (1874–1947), who, like Maud, emigrated to the United States.

Music-loving Maud showed little interest in painting until age 12 or 14, when her father became her first and sole instructor until she attended the Royal Female School of Art, whose mission was to educate “young women of the middle class to obtain an honourable and profitable employment.” George didn’t allow Maud to use oils until she’d mastered drawing and anatomy, working directly from nature and from human, horse, and dog skeletons. “It is for this reason that I have been able to hold my own place among the best of dog painters—no one has ever touched me in my knowledge of anatomy.” He also instilled in her his work ethic of painting daily from 10 till 4.

Maud’s first painting, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884 when she was 21, was Early Morning, a convincing depiction of a nervous herd of deer looking down a misty mountainside, which was sold and exported to Australia. She exhibited 12 more works at the Academy, to her father’s 19 and her uncle Thomas’s 47. Her first commission, by the Squire of Vagnol Park, was a painting of driven grouse.

It’s no coincidence that Earl’s rise in popularity corresponded with Queen Victoria’s patronage of canine companionship. Victoria kept 70 to 100 mostly purebred but not always perfect pet dogs—bulldogs, deerhounds, Pomeranians, retrievers, Saint Bernards, harriers, setters, pointers, terriers, and others. For newly recognized varieties, royal benediction caused their popularity to soar—the collie, for example, after the Queen accepted one named Sharp. A portrait by Maud Earl gave breeds additional authority, and Victoria summoned Earl to Windsor to paint another collie, Snowball, which Earl considered a model sitter. (The painting was later given to the Artists’ War Fund to raise monies through a Christie’s auction for the Boer War’s wounded.) Earl did the same for Welsh springer spaniels when her portrait of two champions served as the frontispiece for the February 1911 Kennel Gazette.

Keeping purebred dogs became an obligatory social distinction of the upper crust. Dog fancying gave rise to competitive show trials, such as “Best looking and best matched brace of Pointers and Setters,” and conformance shows such as Crufts, started in 1886 by Charles Cruft, a former dog biscuit salesman and the son of a London jeweler. Soon, every breeder and owner of a champion dog wanted to immortalize their winner with an Earl portrait. In 1908, Earl moved her studio from St. John’s Wood, London, to Paris, where she had success painting portraits of dogs with their posh owners, and packs of French hunting hounds.

At Earl’s first one-woman show, in 1897 at London’s Graves Galleries, her 70 dog portraits represented an astounding 48 varieties of canines. Asked if she’d painted every kind of dog, she confessed, “I have never painted a Mexican hairless dog or an African dog.” She also painted composite pictures, the springer spaniel, for example, to illustrate the Kennel Club’s Standard of the Breed.

Maud was a knowledgeable dog handler, and her two-day, two-session working method was to pose her subject, held in position by a servant with a leash, on a three-foot-high table with casters. “I study the anatomy of dogs thoroughly. I see the dog when he is standing still and lying down . . . and moving about.” She sketched, made notes, but never used a camera, wanting to see what she saw, and not an image captured by a lens. “Of course, a great deal must be left to the imagination. It is manifestly impossible to pose two greyhounds coursing a hare on a studio,” said Earl.

Earl was already an expert on the line and curve of each breed’s body, the texture of its coat, and its distinct expression, such as the worried look of greyhounds and the twitchy, game-seeking nose of the gundog. With the addition of context details or landscape, it took about a week to complete an oil canvas.

In 1902, Earl began illustrations for William Arkwright’s mammoth Pointer and his Predecessors, which also contained work by her father. Her reputation bolstered, she published her now rare folio of 24 mounted photogravures of prestigious British Hounds and Gundogs. Printed by the Berlin Photographic Company in a limited and signed edition, it accompanied her second one-woman show at Graves. The dog heads, in frontal and profile positions, are loosely sketched, without backgrounds, a style that evolved after 1900, except for paintings titled “in a Landscape.” Then, she conveyed Scottish moorlands and Irish hills far into the distance with impressionistic dapples of soft colors.

Her 1903 Graves exhibition and limited-edition folio of six photogravures was titled Terriers and Toys. In those uncluttered compositions of a spirited style and light touch, Earl’s dogs are carefully drawn with just enough loosely painted detail to suggest a narrative behind the subject’s name, for example, linking it to its homeland. Her appreciation of negative space resulted in balanced, bright, and airy arrangements. The sketchy, unfinished edges on nearly blank backdrops of soft lavender, creamy white, or pale gray give pleasing grace to Earl’s work. Paintings intended to be reproduced as illustrations are especially “clean.” By 1916, settings disappear almost completely.

Earl’s harmonious and coherent compositions are best when presenting more than one subject, such as three borzoi heads or racing greyhounds, or her wind-cutting trio of coursing foxhounds.

With time, Earl’s palette became lighter with her brilliant use of opaque white, as in the coats and snow in her says-it-all painting, Farthest North: The End of the Expedition, of the two surviving sled dogs (out of 40) from Rear Admiral Robert E. Peary’s 1886 Greenland expedition.

Britain’s dog frenzy continued with the crowning of the Prince of Wales as Edward VII in 1901. At their Norfolk estate, Sandringham, he and Queen Alexandra kept borzois, Russian wolfhounds, basset hounds, Clumber spaniels, Norwegian sled dogs, and more—many of which Earl painted. Most famously was the King’s favorite, Caesar of Nott, which newsreels show walking behind his master’s casket in 1911. Earl’s image, Silent Sorrow, of the forlorn fox terrier was reproduced countless times, including in the 1912 book, “by” Caesar, Where’s Master?, followed by “his” book, My Dog Friends, with 12 full-page tipped-in color plates by Earl.

By 1911, her paintings for A. Croxton Smith’s Power of the Dog, with its Pomeranian, chowchow, miniature poodle, and Pekingese, sometimes with a poppy-colored ribbon or pillow to serve as a room’s coordinating color, reflect Earl’s striving for what she called the “decorative value” of her work.

In 1916 Earl emigrated from an England she found unbearably transformed by the Great War, to two studios overlooking Manhattan’s Central Park at the Volney Hotel on East 74th Street. (Dorothy Parker lived there from 1952 and wrote a scorching play, Women of the Corridor, based on the building’s dozens of dog-loving old biddies.) Earl soon began receiving invitations to fine estates in Tennessee and North Carolina to paint the owner’s famous dogs.

Earl cut back on dog portraits and began her very successful “Chinese period,” painting large silk panels and screens with colorfully plumaged birds—blue herons, pink-crested cockatoos, macaws, silver pheasants—against silver- or gold-painted backcloths. Of course, the inevitable happened, and small, flamboyant Asian breeds of dogs worked their way back into Earl’s work, contributing their dynamism and point of view to the composition. During the last years of Earl’s career, she returned to dog portraits in her earlier traditional style.

Brooke Chilvers recently questioned several employees and residents at the Volney, and none had heard of Maud Earl—or Dorothy Parker. But Earl is listed as a “major figure” in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York.

Featured Artwork: Setters on the Moor, 0il on canvas, 20 x 30 inches

Photographs Courtesy William Secord Gallery, New York