by O. Victor Miller

I’ve had hunting dogs all my life.

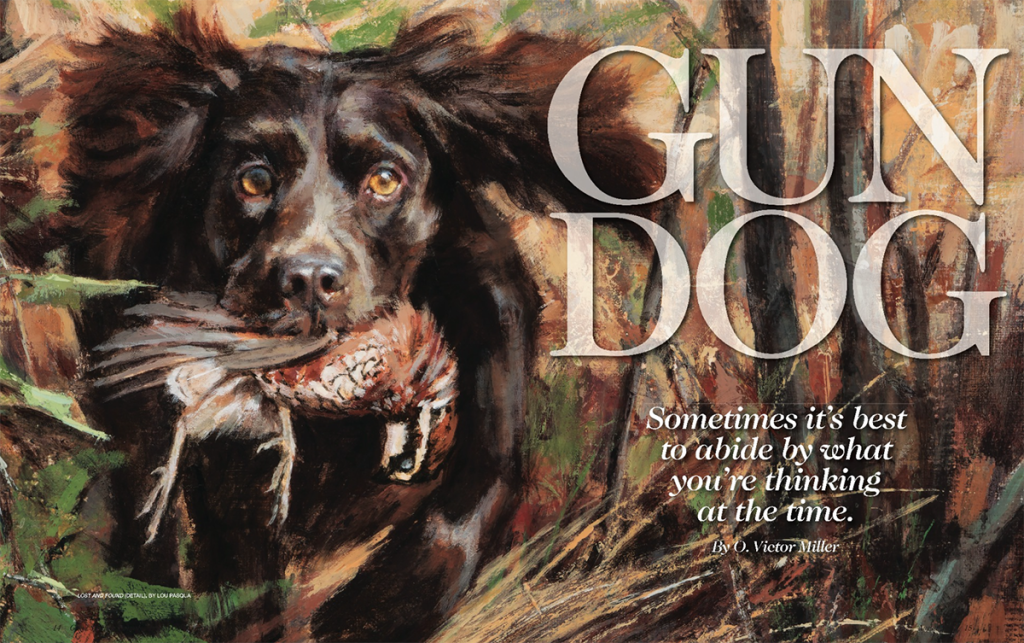

English, Llewellin, and Irish setters. Beagles, Weimaraners, Labs, and Boykin spaniels. The best gun dog I ever had was a Boykin named Clyde Edgerton, the namesake of the North Carolina novelist and a quail hunting buddy of mine. Generally speaking, it’s better to have a good dog named after you than a kid, who’s liable to grow up to disappoint you. I now have a Boykin named Bailey White, another good friend and writer. It’s only friends who I highly esteem who become namesakes for my gun dogs.

When Clyde was just a puppy, I took him into a swampy bottom to let him find a deer I’d shot and marked down. From that day on he became a crackerjack at trailing wounded deer, especially those lost to archery hunters. He’d find the deer, humping away as you dragged it out. Then he’d jump into the bed of the truck and hump it there.

People would call me at night to bring Clyde to trail lost whitetails. One of the guests at Blue Springs Plantation shot a trophy buck that ran off. The next morning, the mistress of the plantation and I rode around in a Jeep, sending Clyde into the swamp bottoms and hedge rows where we thought a wounded deer might go. Finally, we gave up. We sat on a hill talking until I saw movement out of the corner of my eye: Clyde’s little bobtail rising and falling in the broom sedge at the top of the hill. “Yonder’s your buck,” I told Catherine. We drove over to Clyde, who was dry humping the dead deer, panting and grinning ear to ear.

Clyde was my second Boykin spaniel. My first one, Geechee, was killed and eaten by a Florida alligator. My fourth wife asked me to wait a while before getting another dog, but I was so distraught over losing Geechee, I acquired Clyde anyway. I guess I decided I could do without a wife better than I could do without a dog. I know that sounds crazy, but that’s the way I was thinking at the time. I hasten to add that all four of my wives were exemplary women, commonly flawed only by their taste in husbands. I don’t blame them one bit for being unable to live with me. Sometimes I even have trouble living with myself, but I never had any trouble getting along with Clyde. He loved to hunt, would bounce in place when he saw anybody dressed in camouflage or toting a shotgun, and he’d hunt anything. He’d hide when I hid, Clyde would, and stalk when I stalked. When he was a puppy stumbling over himself, I taught him to fetch a rolled-up boot sock tossed down the hall of my Airstream travel trailer, where we lived on a friend of mine’s hunting land and hid out when trouble brewed and my fourth marriage started going south.

I took the puppy from his mother and put him inside my shirt and carried him everywhere I went, to bond with him and make him brave. I even carried him to the classroom, where I taught English at a community college in southwest Georgia. Clyde was a hit with the students. He wandered beneath their desks, chewing their shoelaces. That ain’t the only thing he chewed. He loved to gnaw on computer wires in the language lab, where I went on Saturdays to write fiction. I tried to keep an eye on Clyde. If he made a puddle or a poop, I cleaned it up before I left, but a few administrators had it in for him. They claimed he was a nuisance and a distraction. Imagine that.

The students on campus treated him like a mascot, throwing tennis balls he acquired from the tennis courts and golf balls from the putting green. They taught him to wet retrieve in the president’s fountain and goldfish pool. He’d dive to the bottom to fetch the golf balls. He was a pretty puppy, a dark chocolate with curly ears with tawny highlights and amethyst eyes, so cute the physical education department accepted him as a natural hazard, tolerating him more than they would’ve an ugly dog. But the suits in the administration building lacked humor. They wanted Clyde gone. It was clear none of them had ever owned a gun dog.

Clyde generally went to sleep in the leg well of the desks, both in my office and in the language lab. One Monday morning, when I came in to teach my eight o’clock class, there was crime tape across the entrance doors of the humanities building. Police, press, students, and teachers were crowded outside. No one was allowed to enter until the detectives examined the crime scene. A pervert, they said, had broken into the computer lab and chewed the crotch out of an embroidered foam rubber cushion in Miss Purdy’s, the lab director’s, chair.

Dr. Henry Hart, my veterinarian and hunting pal, castrated Clyde while I assisted. We hoped this would curb the poor pup’s concupiscence. My wife suggested Henry fix me at the same time.

Miss Purdy was in hysterical tears, being consoled. The chairperson of the humanities division arrived just before I did. She asked if anyone had asked Vic Miller about it. “I don’t think Mr. Miller would gnaw the crotch out of Miss Purdy’s seat cushion,” she said. “but he sometimes comes in on weekends. Maybe he observed something that will give the detectives a clue.” When the culprit was revealed, I was advised again that pets were not allowed on campus. “Clyde’s not a pet,” I countered. “He’s a gun dog. And what about the snakes I bring to writing class as subjects for student essays?” I usually brought king snakes and white oak runners, but I had on occasion used a python and a diamondback rattlesnake. I’d found that even the most apathetic student would start putting words on paper when a snake was loose in the classroom and the door was locked. Adrenalin was a good muse.

The suits decided they couldn’t do anything about the snakes, since they were covered by academic freedom statutes. I guess it goes without saying I was tenured at the time and as difficult to manage as Clyde. We both had a hard time sitting still.

As Clyde matured, he developed the trait some puritanical folks found discomfiting. He’d show strangers he was excited to see them by humping their legs. He didn’t discriminate. He was glad to see everybody, including suits in the administration building, who were accustomed to being taken seriously. It’s hard to maintain composure with a humping dog latched on to your leg.

Dr. Henry Hart, my veterinarian and hunting pal, castrated Clyde while I assisted. We hoped this would curb the poor pup’s concupiscence. My wife suggested Henry fix me at the same time. She may’ve been joking, but that was the way she was thinking at the time. In retrospect, I agree that without glandular distractions I might’ve amounted to something. For several days after the procedure, Clyde remained in shock—frightened, timid, and shy. He hunkered down with his bobtail between his legs, refusing to smile. I gave him time to recover, rolling his tennis ball short distances, petting him and reassuring him, and, after a week or so, recover he did.

The only lasting behavioral change was an increased obsession with fetching balls. He wanted to please folks more than ever. I guess he thought if he wasn’t a good dog, he’d get himself castrated again. He became fixated. He’d find any object that could be tossed, carry it to any stranger, and whine piteously until it was picked up and thrown. Castration didn’t alter his method of greeting visitors one bit. He’d still hump the leg of any visitor—Seventh Day Adventist, Colonial Dame, or the girl next door—but his welcome now was altogether without prurience. His greetings were manifestations of pure and unmitigated delight, a doggy dance no more erotic than a platonic hug from a matronly aunt. Now a eunuch, Clyde was pure of heart, though the wife still was not appeased. “Can’t you teach him to just shake hands?” she said. I thought such trivial tricks were beneath a gun dog’s dignity. It wasn’t beneath his dignity, however, to roll in something dead, a common characteristic of hunting dogs the world over.