by Brooke Chilvers

For many years, and for many reasons, we often returned to the historic Compiègne Forest, 55 miles north of Paris.

Virtually every French king, and two self-proclaimed emperors, hunted stag, roe deer and wild boar along its 350 quaintly signposted layons or forestry trails that traverse the 35,620-acre, pond- and lake-studded Forêt de Compiègne. It also shelters a string of picturesque Picardy villages, such as Saint-Jean-aux-Bois with its battered 800-year-old sessile oak, one of the oldest trees in France, and excellent dining establishments whose inviting names include the word Auberge, such as the elegant Auberge du Pont de Rethondes.

We stay in a favorite B&B deep in the woods. I can’t tell you more for risk of spoiling it, except to say that breakfasts are far less lavish since Madame died (too young) last year. But the tall windows and large terraces still overlook green fields replete with a dozen of late summer’s cavorting horses. And if your timing is right in September, you can sleep to the roaring of red stag in rut. This year, while feasting out of a dinner picnic basket, we watched a 12-pointer hustling about his harem of several dozen females. He rolled in mud and tossed the excess off his handsome rack – all just 150 yards away.

We come to paddle the lake below the fairytale Château de Pierrefonds. And to visit, yet again, Emperor Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie’s “Versailles of the Second Empire,” the austere but lovely Château de Compiègne, whose walls are hung with rare imperial hunting scenes, by court artist Louis Godefroy Jadin (1805–1882), depicting outings that counted 120 hounds and 60 horses.

Each time, we also pay tribute at the Clairière de l’Armistice where, on November 11, 1918 at 5:45 a.m., in the converted dining car No. 2419D of his personal railway carriage and mobile HQ, Supreme Allied Commander Maréchal Ferdinand Foch signed the Armistice with the German delegation, thus ending the four-year-plus Great War.

The name, the Glade of the Armistice, rings with bright optimism for enduring peace and the end of warfare for all times. The cost had been devastating — some 20 million military and civilian deaths and about the same number of wounded. In France, one in every 25 inhabitants died; in Great Britain, one in 57, and one of every 30 in Germany.

For the art world, the timing of the war could not have been worse, for exhilarating avant-garde movements were birthing Post-Impressionism, Jugendstil, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, and German Expressionist movements such as Dresden’s Die Brücke, Vienna’s Sezession, and Munich’s Der Blaue Reiter, which included German artists August Macke (1887–1914) and Franz Marc (1880–1916), both killed in battle. Author Tim Cross lists 750 noted poets, composers, playwrights, and artists who were swept away by the Great War, depriving us of their brilliant futures.

Franz Marc was the son of a successful landscape painter; his Alsatian mother was a strict Calvinist with little appreciation for “The Arts.” After completing his military service as a corporal, Marc entered the Munich Academy – a bastion of tradition. But after discovering Impressionism during a three-month stay in Paris, in 1903 he dropped out and forever abandoned an academic style of painting.

Even Impressionism was “too moderate” for Marc, who turned to Cezanne, Gauguin, and Matisse to release himself entirely from reality-based colors. Instead, he attributed symbolic emotional significance to them: “Blue is the male principle, stern and spiritual. Yellow is the female, gentle, cheerful and sensual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy.” Blue and red together express unbearable sorrow, comforted by yellow; blue and orange are always “a harmony of celebration.”

Marc experienced animals empathetically, visualizing their universe through their eyes, asking himself, “How does a horse see the world, how does an eagle, a deer or a dog?” He went so far as to write, “From now on we must stop thinking of animals and plants only in relationship to ourselves and stop portraying them from our point of view in art. That belongs to the past …”

By 1911, true-to-life conventions, including spatial reality, were out the door. In his ethereal Deer in the Snow, his sweeping brushstrokes of the arabesque forms of the deer are harmoniously echoed in the musical, curvy clouds framing them.

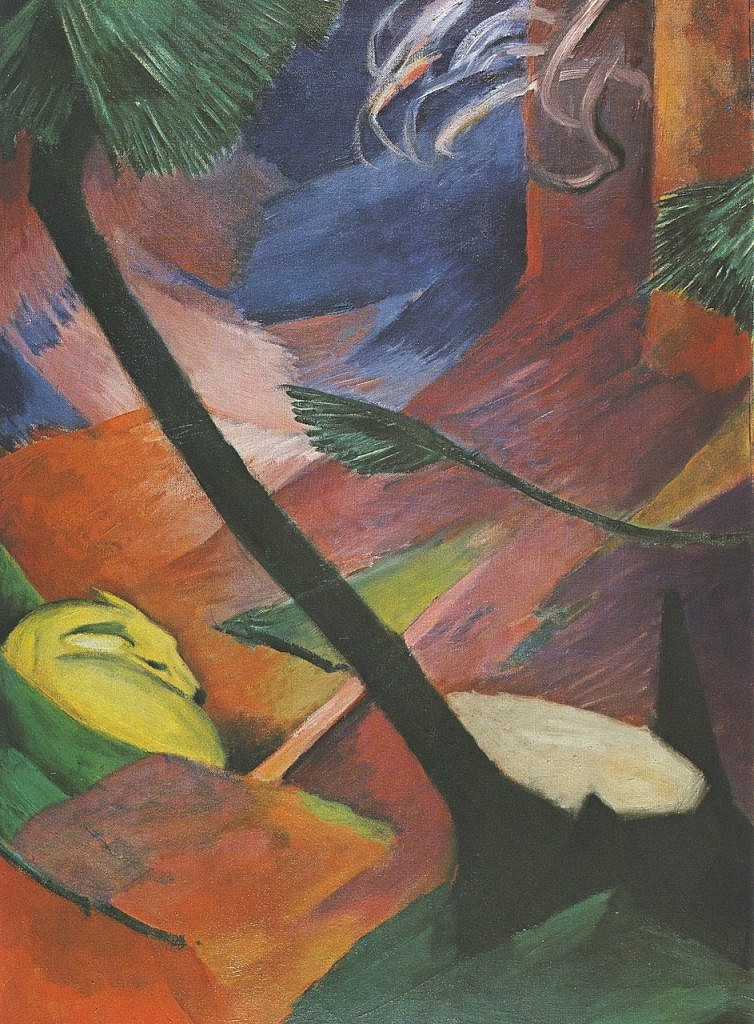

In Deer in the Forest (1912), a sleeping deer is nestled in the fancifully colored woods, protected against a raging wind that has toppled a tree trunk diagonally across the canvas, which allows us to share the deer’s sense of safety from the storm.

Marc’s struggle was internal, too, for like many of his generation he believed that Europe’s materialistic, bourgeois society needed spiritual purification and rebirth through the blood sacrifice of war, and he enlisted as an officer in the German Army reserve. In the first weeks of war, his closest friend, the equally gifted August Macke died during the First Battle of Champagne, along with 45,000 other Germans and twice as many Frenchmen.

Although promoted to lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross, Marc became disillusioned with war, writing his wife, “The ungodly people around me (particularly the men) did not arouse my true feelings, whereas the undefiled vitality of animals called forth everything good in me . . . I found people ‘ugly’ from early on; animals seemed to me more beautiful, more pure.”

After 19 months of service, in March, 1916, while on a horseback reconnaissance near the town of Braquis, 20 kilometres from Verdun, Marc was struck in the head by a grenade fragment. As if he sensed the impending tragedy of his loss to us, in one of his last letters, he wrote, “It is terrible to think of, and all for nothing, for a misunderstanding, for want of being able to make ourselves tolerably understood by our neighbors.”

In 1933, the Nazis declared his works degenerate; many were seized and sold abroad.

On June 22, 1940, in that same forest clearing, in that same dining car, Germany’s victory over France was formalized in the Second Treaty of Compiègne, in the presence of Adolf Hitler himself. Foch’s (in)famous railroad car was hauled off to Berlin for display.

In March, 1945, it was dynamited, destroyed, and buried, while much of Marc’s remaining work was lost in the Allied bombing of Berlin.

______________________________________________________________________________

Brooke Chilvers returned to Picardy to attend the christening of her godson’s first-born child, who “will have to forgive his parents for naming him Tancrède.”