by Brooke Chilvers

Artist David Shepherd (1931–2017) once said that he was attracted to all things “jumbo,” from elephants and airplanes to the steam locomotives whose reign in Great Britain came to an end in 1968 with the dieselization of British Rail.

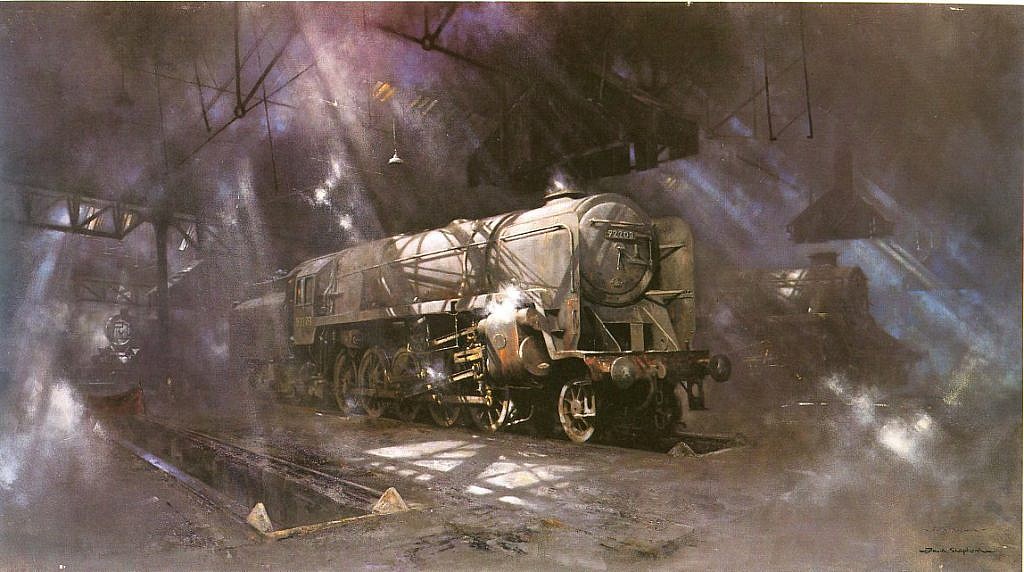

Most of us are familiar with Shepherd’s iconic images of regal wildlife, including the unlimited print, Wise Old Elephant, which sold hundreds of thousands of copies. But his less ubiquitous but equally evocative oil paintings of steam engines and their grubby sheds immortalize that bygone era in our minds. They also display a surprisingly different touch, brushstroke, and feeling than Tsavo’s red dust misting the Big Five.

Although the young Shepherd was no praised child prodigy, his three-year apprenticeship with a hard-working portrait and marine artist named Robin Goodwin taught him everything he needed to know to paint. He writes of his only art education, “I owe him everything”—especially that ‘expressing yourself’ doesn’t pay the bills.” And learning to work eight hours a day, seven days a week, because, Goodwin had made clear, “You’re going to be painting for the tax man, the food bills, and the school fees.” In fact, in his much repeated texts in his many colorful books, he confesses that his formula for success is more hard work than talent.

When success came to Shepherd in the early 1960s, it came full and fast. Two years after seeing his first rhinoceros in Kenya, his exhibition of wildlife works in London sold out in 20 minutes. His sell-out show in New York City in 1967 allowed the artist, his wife Avril, and their four daughters to make a home out of a 16th century farmhouse near Hascombe in Surrey. (It was near here, at Hoe Farm, that Winston Churchill first discovered his love and aptitude for painting while recovering from depression after the Great War catastrophe at Gallipoli.)

Prosperity soon also allowed Shepherd to indulge his childhood passion, handed down from his father, for steam locomotives: “I always preferred to watch trains go by than to build sand castles.” He’d caught the “preservation bug” while painting at the Guilford and Nine Elms railroad sheds, and quickly purchased two of his own engines.

In 1967, for £3,000, he bought an eight-year-old, 140-ton, 1959 BR Standard 9F 2-10-0, No. 92203, one of the last to be built in Swindon, known as the Black Knight. No. 92203 had worked lines in Somerset and Dorset before hauling iron ore from the Liverpool docks.

“The Standard 9 could indeed be termed the ultimate in British steam-locomotive design,” wrote Shepherd of the class that consisted of 251 engines.

For £2,200, he also took possession of the 120-ton, 1954 BR Standard 4MT 4-6-0 No. 75029, the Green Knight, which was retired by British Rail after working the Cambrian Coast Line. He memorializes both engines’ legacies in On Shed – As We Remember Them in the Last Days of Steam.

Now, where to keep his Big Boys? In those still-wonderful years, Shepherd was able to convince a colonel, who convinced British Rail, to let them “in full glory under their own steam” travel from Crewe South locomotive shed in Cheshire, down through the Midlands, to Longmoor Military Camp, where there was an old Nissen hut they could call home. Six years later, in 1974, his two locomotives found a permanent place when Shepherd helped found the East Somerset Railway, at Cranmore near Shepton Mallet in Somerset. With its station, signal box, platforms, and restoration and maintenance teams, today the five-mile heritage steam railway is an important tourist attraction.

Already in the early 1950s Shepherd was swept up by trains and the vast wooden depots and steam sheds that housed them. In 1955 alone, he completed five railway works, all painted on the spot in the sooty, clammy guts of the grimy, bustling sheds at Crewe and Swindon Works, which would soon all be demolished into wastelands rather than preserved. “Every brush mark of these paintings was painted on site, and in the most appalling conditions. Winter, snow, drips…”

Yet, in these steel dungeons, “Lovely harmonies could be found in the cool greys, browns and mauves of the dirty engines.” Reflections of brilliant sunlight came in from surprising places at astonishing angles. With their bright highlights and deep shadows, painting steam for Shepherd was as atmospheric as catching the clouds over the Serengeti.

In the “cathedral-like” atmosphere of works such as Willesden Steam Sheds, Shepherd said, “Here in the gloomy depths of a roundhouse, there was intense beauty of the most dramatic kind if you look for it, through the dirt and the grime. Shafts of sunlight penetrated broken panes of soot-caked glass in the roof, pierced through the steam and smoke and played on pools of green oil on the floor.” As predicted, British Railways would be one of his first clients.

Sensing that the era of steam traction was coming to an end, in 1967 he made dozens of 30-minute “lightning sketches” to serve as reference notes for the resplendent colors of churned grime and metal before the engines were carted away to scrap. To convey their rusty charm, he daubed color over color to recreate the layers of filth, paint, and rust of the neglected giants.

Just as Shepherd placed his kudus and lions in the middle of their natural surroundings, so he did with Over the Forth, the LNER A2 Pacific carrying freight on one of its last runs across the beautiful but aging bridge consisting of 145 acres of steel held in place by 6.5 million rivets.

Shepherd would travel as far as South Africa to paint locomotives. On the very day that steam came to an end in Great Britain, in 1968, he was wild with enthusiasm in the Germiston Loco sheds, sheltering some 200 still-working locomotives, including South African Class S1 080 steam locomotives. In sharp contrast to England, where trains were left in their juice, here, “some were burnished to gleam like jewels.” Shepherd loved all the “shunting, hauling trails, and moving in and out of the shed,” which was filled with choking smoke “which, of course, is part of the glory of steam to someone like me.”

Already in 1967, Shepherd had been commissioned by Anglo American Corporation to paint the portrait of Zambian President (from 1964 to 1991), His Excellency, Dr. Kenneth Kaunda. While Shepherd was on a painting safari in the country’s Luangwa Valley, a professional hunter and his client chanced upon a vintage steam engine locomotive and railway coach in the bush. It turned out to be a vintage (1896) Class 7 3-ft., 6-in., gauge Sharpe Stewart 4-8: ex-South African No. 933; ex-Cape Government Railway No. 39; and ex-Rhodesia Railways. It had spent its old age working for the Zambezi Sawmills Railway, also known as the Mulbezi Railway, carrying timber to Livingstone.

In 1974, Kaunda gave the locomotive and coach to Shepherd in recognition of his donating the proceeds from the sale of seven of his paintings at the 1971 Safari Club International convention for the purchase of a helicopter to fight poaching. On YouTube, you can catch bits of the 1976 BBC special, Last Train to Mulobezi, which shows the locomotive and coach on their 12,000-mile voyage back to England. Today, they live on in the Great Hall of the National Railway Museum in York.

There would be another steam locomotive in Shepherd’s life when South African Railways, in 1991, in exchange for an original oil painting, gave him a 1946 Class 15F, “perhaps one of the most impressive engines ever built anywhere.” He named No. 3052 Avril.

Concluding with Shepherd’s words, that the steam age “didn’t go out in a blaze of glory—it went out in neglect, filth and degradation,” these works have surely helped preserve its place in history, at least in our minds.

Brooke Chilvers learned that a number of aircraft and railway paintings have recently been donated to the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation for sale, with proceeds being used to protect and conserve wildlife and their habitats. Contact Jessica Donald, Art Manager of the DSWF, at [email protected].