by Brooke Chilvers

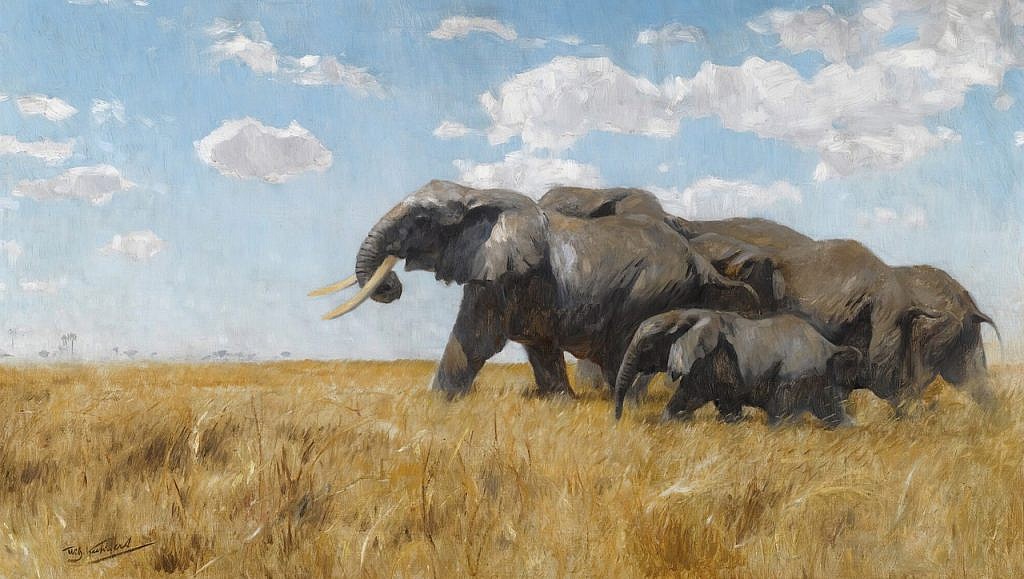

Each time we return to Tanzania – from 1994, when we were tasked with building a primitive safari camp in Tarangire Game Reserve, to our recent family photographic safari, where we were headache-free clients instead of stressed-out organizers – I fall in love all over again with German wildlife artist and hunter Friedrich Wilhelm Kuhnert (1865–1926).

In fact, there were moments, especially in the Rungwa Game Reserve and Ruaha National Park, and even in the bustling town of Iringa where we kitted out in 1998, when I sometimes felt I was literally walking in Wilhelm’s footsteps.

It was early August that year when our usually laid-back Indian shopkeeper was suddenly ushering us with urgency into his family’s colorful quarters to watch on TV the aftermath of the bombing by Al-Qaeda of the American embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi that killed 224 people. We’d left Dar only three days earlier! It felt like a miracle when our family of French clients did not cancel their safari in Rungwa.

Yet through my tears, I could still feel the pull of pure air that captured the clear African light Kuhnert experienced during his four painting and hunting safaris, between 1891 and 1912, to German East Africa (G.E.A.) and Sudan. If quartered here, I knew I could be happy, looking for traces of Kuhnert, seeing the river and rocky hills through his eyes.

Unfortunately, his travel-painting-hunting diaries from Europe, East Africa, and India remain unpublished, and his illustrated 1920 African narrative, Im Land Meiner Modelle, has never been translated. Alongside his narratives of confronting elephant, lion and Cape buffalo, he recorded accidents, illnesses, loads lost in rivers, and both the kindness and truculence of natives. He described the shapes of umbrella acacias and shimmering yellow fever trees, and the misery of painting during East Africa’s two rainy seasons, with their clouds of annoying insects.

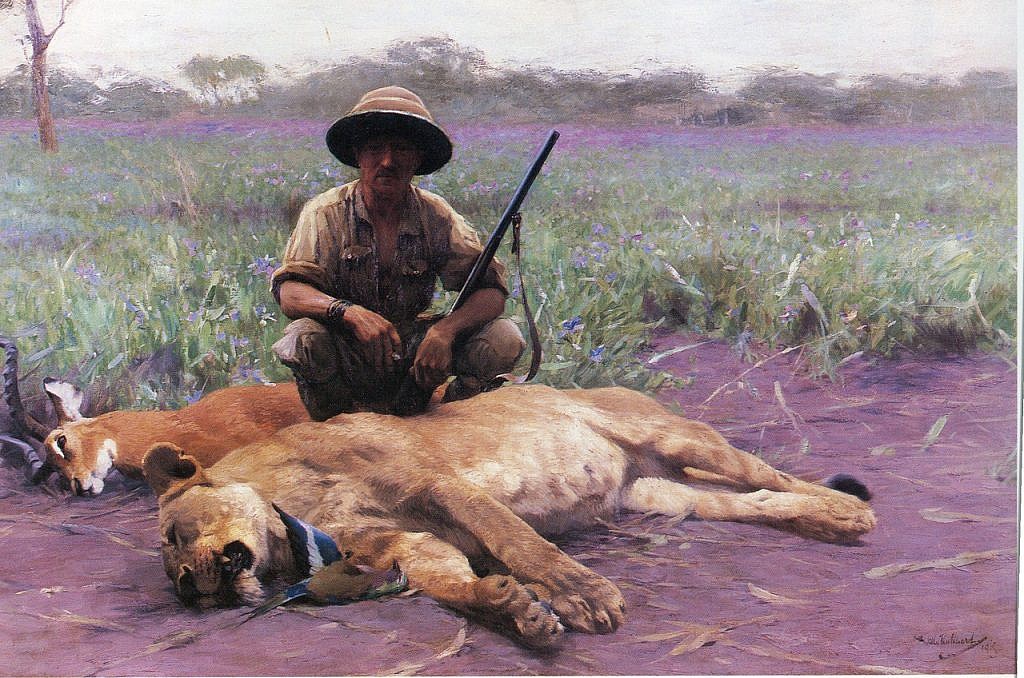

Although the artist complained of having to exchange his brushes for his double-barreled rifles to fill the bellies of his 60 ever-hungry men, with the passion of a hunter he kept track of his stalks, shooting distances, and the locations of recovered bullets.

Kuhnert described and measured his subjects, from horn tips to tail hairs, with precision. Yet he translated their environment with the vision of a landscape artist, chronicling African skies and weather, and painting themin tropical luminescence, sometimes substituting blue skies for dull ones to offset the striking markings of giraffes and zebras, and fields exploding with African impatiens when the Masai steppe is in bloom.

Europe’s first plein-air artist to portray Africa’s wildlife, landscapes, and people was born in German Upper Silesia — today, southern Poland. Despite an obvious early talent, his civil-servant father obliged him to apprentice in a machining factory, while he studied Holbein and Vermeeron his own. At 17, with help from an uncle, he moved to Berlin, where he supported himself as a portrait artist and calligrapher.

Only two years later, the self-taught student was accepted into the prestigious Berlin Royal Academy of Art. During his four-year classically structured Studium, Kuhnert learned drawing with pencil, charcoal, and chalk; human anatomy and proportion; perspective and shading. No doubt he was influenced by his landscape instructor, Ferdinand Bellermann (1814–1889), who’d spent four years in Venezuela depicting its rainforests in exotic, but scientifically accurate, landscapes.

Kuhnert studied animal painting under Paul Meyerheim (1842–1915), who’d done credible works of lions from circuses and zoos, and taught the connection between skeleton and musculature to movement and expression, to fur and its changing sheen.

Success arrived the same year, 1885, that Chancellor Otto von Bismarck formalized Germany’s position in the “Scramble for Africa,” by granting an imperial charter to the protectorate of German East Africa (1885–1919), located between Great Britain’s Kenya colony and Portugal’s Mozambique, and encompassing yesterday’s Tanganyika and today’s Rwanda and Burundi.

Five years later, the 27-year-old artist set off on his first 18-month African safari, funded by earnings from illustrating a dictionary of animals.

From Tanga, on the Indian Ocean near the Kenya border, Kuhnert walked inland along the trails of Arab slavers, through Masailand to the foothills of Kilimanjaro. His 25 porters carried his camp, staples, hunting guns, trade goods, and extensive art supplies.

His second safari, in 1905, took him from Dar es Salaam to the Southern Highlands, moving between today’s Ruaha National Park and the Selous Game Reserve. (This is where I felt him most.) Caught up in a native uprising against colonial tax and labor policies, the wild-hearted artist was confined for weeks in primitive garrison posts in Mahende and Iringa, and painted battles scenes instead of wild beasts.

Six years later, at the suggestion of a Leipzig newspaper, Kuhnert accompanied Friedrich August III, the last king of Saxony, on safari in the British-Egyptian Sudan. But the constraints and protocol perturbed him, and it was not satisfying.

He returned to G.E.A. in 1912, lingering for weeks in game-rich spots with reliable water. His journals convey his feelings, torn between hunting and painting: “Although the hunter in me has a difficult time overcoming the desire to shoot, the artist in me is stronger, and I have come just to observe as much as possible.”

Although camp meat also served as models, Kuhnert’s impressionistic realism was painterly rather than zealously scientific. He employed loosely painted grasses and fallen deadwood as compositional tools, and created tone or mood by concentrating light and dark areas in different parts of the canvas. A line of riverine forest or islands of worn mountains in the distance suggest Africa’s far horizons.

Kuhnert loved living as free as his subjects, whose body language and physiognomy he noted is not the same as caged zoo animals. Despite his wanderlust, he married an 18-year-old maiden and fathered a single daughter. He was often gone for years at a time and they divorced in 1909, while he was abroad.

Kuhnert’s field knowledge led to his illustrating major zoological works, hunting narratives by science-oriented sportsmen, and even the memoirs of G.E.A.’s first governor, Count Adolf von Götzen, whose bloody handling of the 1905 Maji Maji Rebellion Kuhnert had accidentally experienced first-hand.

The Great War, and possibly age and a second marriage, ended his travels to Africa.

I can see him, in the comfort of his Berlin studio, when a misshapen breeze awakens a gut-felt yearning for Africa’s light and sound. Back in Arusha in 2022, with Kilimanjaro peeking back at us, despite the blood-soaked images embedded in my mind from that day in Iringa, I fell in love with Africa, and Kuhnert, yet again.

Brooke Chilvers was a vice-president of the International Professional Hunters Association (IPHA) for many years, and is an honorary member of the African Professional Hunters Association (APHA).

Thanks, always, to Russell Fink for images.