by Brooke Chilvers

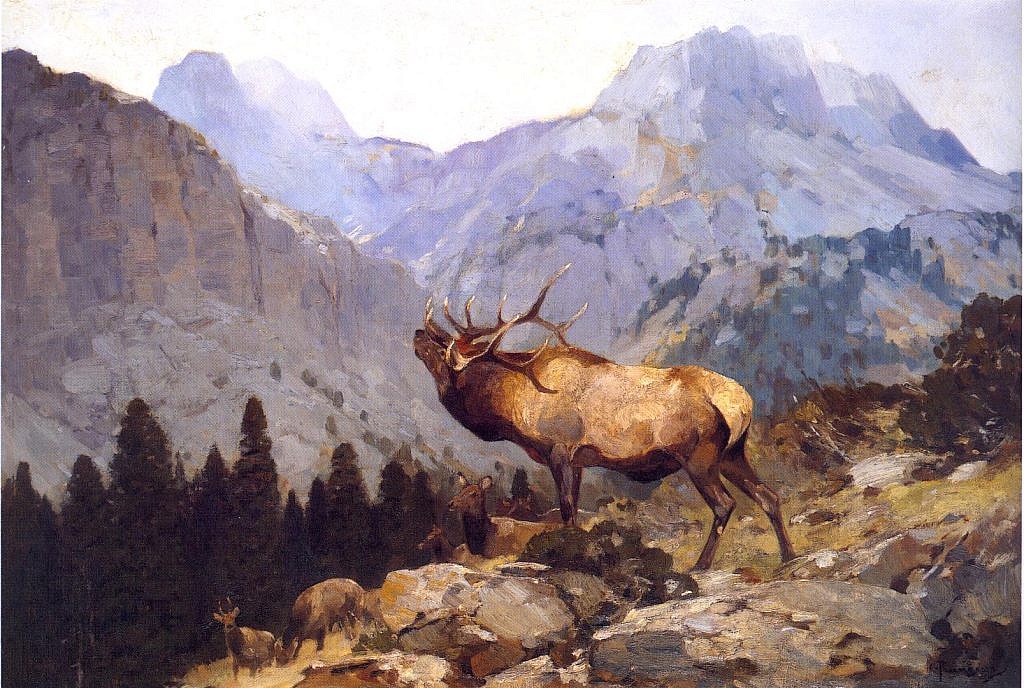

It is always thrilling to see works by hard-to-find Carl Rungius (1869–1959).

More than a dozen years ago, I was on the trail of the German-born American artist and traveled to Calgary, Alberta, in the dead of winter to visit the Glenbow Museum. The museum’s 1985 publications, Carl Rungius, Painter of the Western Wilderness, followed by Carl Rungius – Artist and Sportsman in 2001, had led me to believe I would find a gallery full of Rungius’s caribou and mule deer, grizzly bears and Dall sheep. In fact, I was sure his entire studio would be on display, since the museum’s founder had purchasd the entire Rungius estate down to the last pencil, including the contents of both his New York and Banff studios.

But not a single original Rungius was on display. I toured the permanent collection, bought a scarf with flying geese, and said good-bye to Calgary, wondering what the heck had happened to Rungius’s presence. A recent search of the museum’s website yielded not a single mention of the artist.

Subsequent research led me to the Netherlands, to the bustling, brick-built, beer-making town of Enschede and the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, where I again expected at least a wall of Rungius paintings. A chunk of the Van Heek family’s collection that went into founding the museum included extensive wildlife works by Rungius, Wilhelm Kuhnert (1865-1926), Richard Friese (1854-1918), and Bruno Liljefors (1860-1939). But Rungius et al., were also absent from this museum’s walls and website; the last time they saw light in Enschede was during a 2015 exhibition.

Curator Dr. Paul Knolle deeply appreciated their innovative approach to portraying animals within their natural habitat. He took us down into the cool corridors of carefully archived paintings where, for several hours, we slid out racks of paintings and opened drawers with insightful sketches by all four artists. Gentle reader, I shed tears of joy while beholding these wonderful paintings that now live underground.

We talked of the importance of such fine examples of “sporting art” finding a new audience. And all these years later, the National Sporting Library and Museum is exhibiting works by these artists in cooperation with the Twenthe Museum and the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. As Dr. Adam Duncan Harris, curator of the on-going Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné, put it: “The work of these four artists established a vision of wildlife and wilderness that remains with us today and had a tremendous influence on wildlife artists of the 20th century.”

Rungius joked that he was “born American,” but in fact he was born in rural Rixdorf near Berlin, the first of nine children of a Lutheran pastor. Carl took to skinning feral cats in order to meticulously draw their exposed musculature and boiled skeletons. A poor scholar, he instead completed a year’s military service, which paid off over 50 years of shooting big-game species in Wyoming, New Brunswick, the Yukon, and the Canadian Rockies, in order to portray them.

Although Rungius attended the Berlin Art Academy, his father insisted he also learn the trade of house painter, so he studied ornamental design and painted decorative ceilings to pay his bills. He learned animal anatomy from painting horses at the glue factory, and animal expression, behavior, and movement from the residents of the Berlin zoo.